51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrians look for survivors amid the rubble of a building targeted by a missile in the al-Mashhad neighborhood of Aleppo on January 7, 2013.

Hide Caption

26 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebels launch a missile near the Abu Baker brigade in Al-Bab, Syria, on January 16, 2013.

Hide Caption

27 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

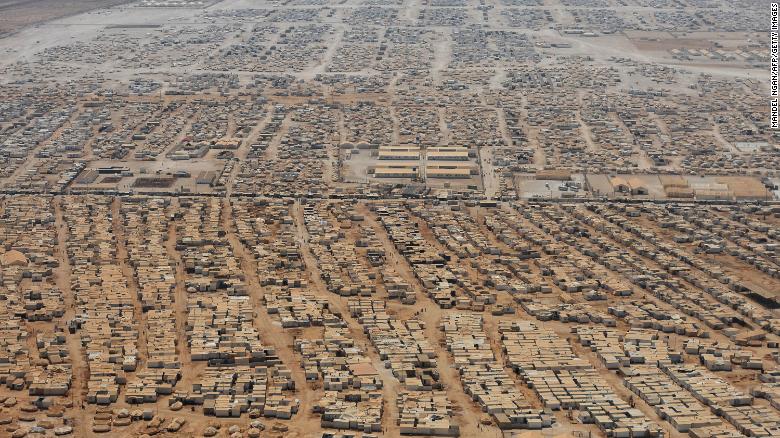

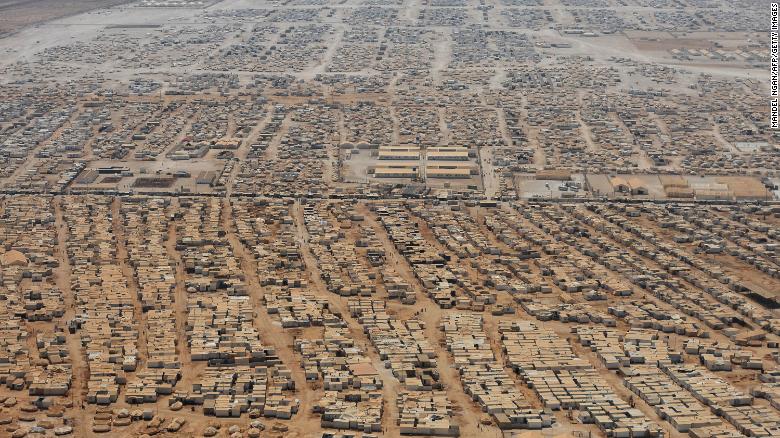

An aerial view shows the Zaatari refugee camp near the Jordanian city of Mafraq on July 18, 2013.

Hide Caption

28 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A handout image released by the Syrian opposition's Shaam News Network shows people inspecting bodies of children and adults who rebels claim were killed in a toxic gas attack by pro-government forces on August 21, 2013. A week later, U.S Secretary of State John Kerry said U.S. intelligence information found that 1,429 people were killed in the chemical weapons attack, including more than 400 children. Al-Assad's government claimed that jihadists fighting with the rebels carried out the chemical weapons attacks to turn global sentiments against it.

Hide Caption

29 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

The U.N. Security Council passes a resolution September 27, 2013, requiring Syria to eliminate its arsenal of chemical weapons. Al-Assad said he would abide by the resolution.

Hide Caption

30 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Residents run from a fire at a gasoline and oil shop in Aleppo's Bustan Al-Qasr neighborhood on October 20, 2013. Witnesses said the fire was caused by a bullet from a pro-government sniper.

Hide Caption

31 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrian children wait as doctors perform medical checkups at a refugee center in Sofia, Bulgaria, on October 26, 2013.

Hide Caption

32 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An injured man is helped following an airstrike in Aleppo's Maadi neighborhood on December 17, 2013.

Hide Caption

33 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Residents wait to receive food aid distributed by the U.N. Relief and Works Agency at the besieged al-Yarmouk camp, south of Damascus, on January 31, 2014.

Hide Caption

34 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A man holds a baby who was rescued from rubble after an airstrike in Aleppo on February 14, 2014.

Hide Caption

35 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A U.S. ship staff member wears personal protective equipment at a naval airbase in Rota, Spain, on April 10, 2014. A former container vessel was fitted out with at least $10 million of gear to let it take on about 560 metric tons of Syria's most dangerous chemical agents and sail them out to sea, officials said.

Hide Caption

36 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Free Syrian Army fighter fires a rocket-propelled grenade during heavy clashes in Aleppo on April 27, 2014.

Hide Caption

37 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A giant poster of al-Assad is seen in Damascus on May 31, 2014, ahead of the country's presidential elections. He received 88.7% of the vote in the country's first election after the civil war broke out.

Hide Caption

38 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebel fighters execute two men on July 25, 2014, in Binnish, Syria. The men were reportedly charged by an Islamic religious court with detonating several car bombs.

Hide Caption

39 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Photographs of victims of the Assad regime are displayed as a Syrian army defector known as "Caesar," center, appears in disguise to speak before the House Foreign Affairs Committee in Washington. The July 31, 2014, briefing was called "Assad's Killing Machine Exposed: Implications for U.S. Policy." Caesar, apparently a witness to the regime's brutality, has smuggled more than 50,000 photographs depicting the torture and execution of more than 10,000 dissidents. CNN cannot independently confirm the authenticity of the photos, documents and testimony referenced in the report.

Hide Caption

40 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Volunteers remove a dead body from under debris after shelling in Aleppo on August 29, 2014. According to the Syrian Civil Defense, barrel bombs are now the greatest killer of civilians in many parts of Syria. The White Helmets are a humanitarian organization that tries to save lives and offer relief.

Hide Caption

41 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Medics tend to a man's injuries at a field hospital in Douma after airstrikes on September 20, 2014.

Hide Caption

42 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A long-exposure photograph shows a rocket being launched in Aleppo on October 5, 2014.

Hide Caption

43 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A man gives medical assistance as two wounded children wait nearby at a field hospital in Douma on February 2, 2015.

Hide Caption

44 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebel fighters dig caves in the mountains for bomb shelters in the northern countryside of Hama on March 9, 2015.

Hide Caption

45 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Nusra Front fighters inspect a helicopter belonging to pro-government forces after it crashed in the rebel-held Idlib countryside on March 22, 2015.

Hide Caption

46 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Syrian boy receives treatment at a local hospital following an alleged chlorine gas attack in the Idlib suburb of Jabal al-Zawia on April 27, 2015.

Hide Caption

47 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Syrian child fleeing the war gets lifted over fences to enter Turkish territory illegally near a border crossing at Akcakale, Turkey, on June 14, 2015.

Hide Caption

48 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A refugee carries mattresses as he re-enters Syria from Turkey on June 22, 2015, after Kurdish People's Protection Units regained control of the area around Tal Abyad, Syria, from ISIS.

Hide Caption

49 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A man's body lies in the back of van as people search for the injured after airstrikes allegedly by the Syrian government on a market in a rebel-held Eastern Ghouta town on August 31, 2015.

Hide Caption

50 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A sandstorm blows over damaged buildings in the rebel-held area of Douma, east of Damascus, on September 7, 2015.

Hide Caption

51 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Pro-government protesters hold pictures of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his late father, Hafez al-Assad, during a rally in Damascus, Syria, on March 18, 2011. Bashar al-Assad has ruled Syria since 2000, when his father passed away following 30 years in charge. An anti-regime uprising that started in March 2011 has spiraled into civil war. The United Nations estimates more than 220,000 people have been killed.

Hide Caption

1 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Hide Caption

2 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An injured man lying in the back of a vehicle is rushed to a hospital in Daraa, south of Damascus, on March 23, 2011. Violence flared in Daraa after a group of teens and children were arrested for writing political graffiti. Dozens of people were killed when security forces cracked down on demonstrations.

Hide Caption

3 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Anti-government protesters demonstrate in Daraa on March 23, 2011. In response to continuing protests, the Syrian government announced several plans to appease citizens.

Hide Caption

4 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrian children walk over bricks stored for road repairs during a spontaneous protest June 15, 2011, at a refugee camp near the Syrian border in Yayladagi, Turkey.

Hide Caption

5 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Jamal al-Wadi of Daraa speaks in Istanbul on September 15, 2011, after an alignment of Syrian opposition leaders announced the creation of a Syrian National Council -- their bid to present a united front against al-Assad's regime and establish a democratic system.

Hide Caption

6 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Suicide bombs hit two security service bases in Damascus on December 23, 2011, killing at least 44 people and wounding 166.

Hide Caption

7 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Supporters of al-Assad celebrate during a referendum vote in Damascus on February 26, 2012. Opposition activists reported at least 55 deaths across the country as Syrians headed to the polls. Analysts and protesters widely described the constitutional referendum as a farce. "Essentially, what (al-Assad's) done here is put a piece of paper that he controls to a vote that he controls so that he can try and maintain control," a U.S. State Department spokeswoman said.

Hide Caption

8 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrian refugees walk across a field in Syria before crossing into Turkey on March 14, 2012.

Hide Caption

9 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An injured man gets treated in a Damascus neighborhood on April 3, 2012.

Hide Caption

10 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

People gather on May 26, 2012, at a mass burial for victims reportedly killed by Syrian forces in Syria's Houla region. U.N. officials confirmed that more than 100 Syrian civilians were killed, including nearly 50 children. Syria's government denied its troops were behind the bloodbath.

Hide Caption

11 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebel fighters with the Free Syrian Army capture a police officer in Aleppo, Syria, who they believed to be pro-regime militiaman on July 31, 2012. Dozens of officers were reportedly killed as rebels seized police stations in the city.

Hide Caption

12 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Free Syrian Army fighter runs for cover as a Syrian Army tank shell hits a building across the street during clashes in the Salaheddine neighborhood of central Aleppo on August 17, 2012.

Hide Caption

13 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Family members mourn the deaths of their relatives in front of a field hospital in Aleppo on August 21, 2012.

Hide Caption

14 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Syrian man carrying grocery bags dodges sniper fire in Aleppo as he runs through an alley near a checkpoint manned by the Free Syrian Army on September 14, 2012.

Hide Caption

15 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Free Syrian Army fighters are reflected in a mirror they use to see a Syrian Army post only 50 meters away in Aleppo on September 16, 2012.

Hide Caption

16 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Smoke rises over the streets after a mortar bomb from Syria landed in the Turkish border village of Akcakale on October 3, 2012. Five people were killed. In response, Turkey fired on Syrian targets and its parliament authorized a resolution giving the government permission to deploy soldiers to foreign countries.

Hide Caption

17 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Syrian rebel walks inside a burnt section of the Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo hours before the Syrian army retook control of the complex on October 14, 2012.

Hide Caption

18 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Relatives of Syrian detainees who were arrested for participating in anti-government protests wait in front of a police building in Damascus on October 24, 2012. The Syrian government said it released 290 prisoners.

Hide Caption

19 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An Israeli tank crew sits on the Golan Heights overlooking the Syrian village of Breqa on November 6, 2012. Israel fired warning shots toward Syria after a mortar shell hit an Israeli military post. It was the first time Israel fired on Syria across the Golan Heights since the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Hide Caption

20 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebels celebrate next to the remains of a Syrian government fighter jet that was shot down at Daret Ezza, on the border of the provinces of Idlib and Aleppo, on November 28, 2012.

Hide Caption

21 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Smoke rises in the Hanano and Bustan al-Basha districts in Aleppo as fighting continues through the night on December 1, 2012.

Hide Caption

22 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

The bodies of three children are laid out for identification by family members at a makeshift hospital in Aleppo on December 2, 2012. The children were allegedly killed in a mortar shell attack that landed close to a bakery in the city.

Hide Caption

23 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A father reacts after the deaths of two of his children in Aleppo on January 3, 2013.

Hide Caption

24 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A rebel fighter prepares the wires of a car-mounted camera used to spy on Syrian government forces while his comrade smokes a cigarette in Aleppo's Bab al-Nasr district on January 7, 2013.

Hide Caption

25 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrians look for survivors amid the rubble of a building targeted by a missile in the al-Mashhad neighborhood of Aleppo on January 7, 2013.

Hide Caption

26 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebels launch a missile near the Abu Baker brigade in Al-Bab, Syria, on January 16, 2013.

Hide Caption

27 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An aerial view shows the Zaatari refugee camp near the Jordanian city of Mafraq on July 18, 2013.

Hide Caption

28 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A handout image released by the Syrian opposition's Shaam News Network shows people inspecting bodies of children and adults who rebels claim were killed in a toxic gas attack by pro-government forces on August 21, 2013. A week later, U.S Secretary of State John Kerry said U.S. intelligence information found that 1,429 people were killed in the chemical weapons attack, including more than 400 children. Al-Assad's government claimed that jihadists fighting with the rebels carried out the chemical weapons attacks to turn global sentiments against it.

Hide Caption

29 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

The U.N. Security Council passes a resolution September 27, 2013, requiring Syria to eliminate its arsenal of chemical weapons. Al-Assad said he would abide by the resolution.

Hide Caption

30 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Residents run from a fire at a gasoline and oil shop in Aleppo's Bustan Al-Qasr neighborhood on October 20, 2013. Witnesses said the fire was caused by a bullet from a pro-government sniper.

Hide Caption

31 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrian children wait as doctors perform medical checkups at a refugee center in Sofia, Bulgaria, on October 26, 2013.

Hide Caption

32 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An injured man is helped following an airstrike in Aleppo's Maadi neighborhood on December 17, 2013.

Hide Caption

33 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Residents wait to receive food aid distributed by the U.N. Relief and Works Agency at the besieged al-Yarmouk camp, south of Damascus, on January 31, 2014.

Hide Caption

34 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A man holds a baby who was rescued from rubble after an airstrike in Aleppo on February 14, 2014.

Hide Caption

35 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A U.S. ship staff member wears personal protective equipment at a naval airbase in Rota, Spain, on April 10, 2014. A former container vessel was fitted out with at least $10 million of gear to let it take on about 560 metric tons of Syria's most dangerous chemical agents and sail them out to sea, officials said.

Hide Caption

36 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Free Syrian Army fighter fires a rocket-propelled grenade during heavy clashes in Aleppo on April 27, 2014.

Hide Caption

37 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A giant poster of al-Assad is seen in Damascus on May 31, 2014, ahead of the country's presidential elections. He received 88.7% of the vote in the country's first election after the civil war broke out.

Hide Caption

38 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebel fighters execute two men on July 25, 2014, in Binnish, Syria. The men were reportedly charged by an Islamic religious court with detonating several car bombs.

Hide Caption

39 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Photographs of victims of the Assad regime are displayed as a Syrian army defector known as "Caesar," center, appears in disguise to speak before the House Foreign Affairs Committee in Washington. The July 31, 2014, briefing was called "Assad's Killing Machine Exposed: Implications for U.S. Policy." Caesar, apparently a witness to the regime's brutality, has smuggled more than 50,000 photographs depicting the torture and execution of more than 10,000 dissidents. CNN cannot independently confirm the authenticity of the photos, documents and testimony referenced in the report.

Hide Caption

40 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Volunteers remove a dead body from under debris after shelling in Aleppo on August 29, 2014. According to the Syrian Civil Defense, barrel bombs are now the greatest killer of civilians in many parts of Syria. The White Helmets are a humanitarian organization that tries to save lives and offer relief.

Hide Caption

41 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Medics tend to a man's injuries at a field hospital in Douma after airstrikes on September 20, 2014.

Hide Caption

42 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A long-exposure photograph shows a rocket being launched in Aleppo on October 5, 2014.

Hide Caption

43 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A man gives medical assistance as two wounded children wait nearby at a field hospital in Douma on February 2, 2015.

Hide Caption

44 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebel fighters dig caves in the mountains for bomb shelters in the northern countryside of Hama on March 9, 2015.

Hide Caption

45 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Nusra Front fighters inspect a helicopter belonging to pro-government forces after it crashed in the rebel-held Idlib countryside on March 22, 2015.

Hide Caption

46 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Syrian boy receives treatment at a local hospital following an alleged chlorine gas attack in the Idlib suburb of Jabal al-Zawia on April 27, 2015.

Hide Caption

47 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Syrian child fleeing the war gets lifted over fences to enter Turkish territory illegally near a border crossing at Akcakale, Turkey, on June 14, 2015.

Hide Caption

48 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A refugee carries mattresses as he re-enters Syria from Turkey on June 22, 2015, after Kurdish People's Protection Units regained control of the area around Tal Abyad, Syria, from ISIS.

Hide Caption

49 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A man's body lies in the back of van as people search for the injured after airstrikes allegedly by the Syrian government on a market in a rebel-held Eastern Ghouta town on August 31, 2015.

Hide Caption

50 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A sandstorm blows over damaged buildings in the rebel-held area of Douma, east of Damascus, on September 7, 2015.

Hide Caption

51 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Pro-government protesters hold pictures of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his late father, Hafez al-Assad, during a rally in Damascus, Syria, on March 18, 2011. Bashar al-Assad has ruled Syria since 2000, when his father passed away following 30 years in charge. An anti-regime uprising that started in March 2011 has spiraled into civil war. The United Nations estimates more than 220,000 people have been killed.

Hide Caption

1 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Hide Caption

2 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An injured man lying in the back of a vehicle is rushed to a hospital in Daraa, south of Damascus, on March 23, 2011. Violence flared in Daraa after a group of teens and children were arrested for writing political graffiti. Dozens of people were killed when security forces cracked down on demonstrations.

Hide Caption

3 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Anti-government protesters demonstrate in Daraa on March 23, 2011. In response to continuing protests, the Syrian government announced several plans to appease citizens.

Hide Caption

4 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrian children walk over bricks stored for road repairs during a spontaneous protest June 15, 2011, at a refugee camp near the Syrian border in Yayladagi, Turkey.

Hide Caption

5 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Jamal al-Wadi of Daraa speaks in Istanbul on September 15, 2011, after an alignment of Syrian opposition leaders announced the creation of a Syrian National Council -- their bid to present a united front against al-Assad's regime and establish a democratic system.

Hide Caption

6 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Suicide bombs hit two security service bases in Damascus on December 23, 2011, killing at least 44 people and wounding 166.

Hide Caption

7 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Supporters of al-Assad celebrate during a referendum vote in Damascus on February 26, 2012. Opposition activists reported at least 55 deaths across the country as Syrians headed to the polls. Analysts and protesters widely described the constitutional referendum as a farce. "Essentially, what (al-Assad's) done here is put a piece of paper that he controls to a vote that he controls so that he can try and maintain control," a U.S. State Department spokeswoman said.

Hide Caption

8 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrian refugees walk across a field in Syria before crossing into Turkey on March 14, 2012.

Hide Caption

9 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An injured man gets treated in a Damascus neighborhood on April 3, 2012.

Hide Caption

10 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

People gather on May 26, 2012, at a mass burial for victims reportedly killed by Syrian forces in Syria's Houla region. U.N. officials confirmed that more than 100 Syrian civilians were killed, including nearly 50 children. Syria's government denied its troops were behind the bloodbath.

Hide Caption

11 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebel fighters with the Free Syrian Army capture a police officer in Aleppo, Syria, who they believed to be pro-regime militiaman on July 31, 2012. Dozens of officers were reportedly killed as rebels seized police stations in the city.

Hide Caption

12 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Free Syrian Army fighter runs for cover as a Syrian Army tank shell hits a building across the street during clashes in the Salaheddine neighborhood of central Aleppo on August 17, 2012.

Hide Caption

13 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Family members mourn the deaths of their relatives in front of a field hospital in Aleppo on August 21, 2012.

Hide Caption

14 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Syrian man carrying grocery bags dodges sniper fire in Aleppo as he runs through an alley near a checkpoint manned by the Free Syrian Army on September 14, 2012.

Hide Caption

15 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Free Syrian Army fighters are reflected in a mirror they use to see a Syrian Army post only 50 meters away in Aleppo on September 16, 2012.

Hide Caption

16 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Smoke rises over the streets after a mortar bomb from Syria landed in the Turkish border village of Akcakale on October 3, 2012. Five people were killed. In response, Turkey fired on Syrian targets and its parliament authorized a resolution giving the government permission to deploy soldiers to foreign countries.

Hide Caption

17 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A Syrian rebel walks inside a burnt section of the Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo hours before the Syrian army retook control of the complex on October 14, 2012.

Hide Caption

18 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Relatives of Syrian detainees who were arrested for participating in anti-government protests wait in front of a police building in Damascus on October 24, 2012. The Syrian government said it released 290 prisoners.

Hide Caption

19 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

An Israeli tank crew sits on the Golan Heights overlooking the Syrian village of Breqa on November 6, 2012. Israel fired warning shots toward Syria after a mortar shell hit an Israeli military post. It was the first time Israel fired on Syria across the Golan Heights since the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Hide Caption

20 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Rebels celebrate next to the remains of a Syrian government fighter jet that was shot down at Daret Ezza, on the border of the provinces of Idlib and Aleppo, on November 28, 2012.

Hide Caption

21 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Smoke rises in the Hanano and Bustan al-Basha districts in Aleppo as fighting continues through the night on December 1, 2012.

Hide Caption

22 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

The bodies of three children are laid out for identification by family members at a makeshift hospital in Aleppo on December 2, 2012. The children were allegedly killed in a mortar shell attack that landed close to a bakery in the city.

Hide Caption

23 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A father reacts after the deaths of two of his children in Aleppo on January 3, 2013.

Hide Caption

24 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

A rebel fighter prepares the wires of a car-mounted camera used to spy on Syrian government forces while his comrade smokes a cigarette in Aleppo's Bab al-Nasr district on January 7, 2013.

Hide Caption

25 of 51

51 photos: Syria's civil war in pictures

Syrians look for survivors amid the rubble of a building targeted by a missile in the al-Mashhad neighborhood of Aleppo on January 7, 2013.

Hide Caption

26 of 51

Peter R. Neumann is professor of Security Studies and director of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalization (ICSR) at King's College London.

London (CNN)Much has been written about the young men and women who join the Islamic State. We are familiar with their biographies and pathways, backgrounds and motivations.

But virtually nothing is known about those who quit: the "defectors" who didn't like what they saw, abandoned their comrades and fled the Islamic State. Yet their stories could be key to stopping the flow of foreign fighters, countering the group's propaganda and exposing its lies and hypocrisy.

For a short paper, I collected all published stories about people who have left the Islamic State and spoken about their defection. I discovered a total of 58 -- a sizable number but probably only a fraction of those who are disillusioned or ready to leave.

They are a new and growing phenomenon. Of the 58 cases, nearly two thirds of the defections took place in the year 2015. One third happened during the summer months alone.

The defectors' experiences are diverse. Not everyone has become a fervent supporter of liberal democracy. Some may, in fact, have committed crimes. They were all, at some point, enthusiastic supporters of the most violent and viciously totalitarian organization of our age. Yet they are now its worst enemies.

The quality of their testimony varies, and the precise circumstances and reasons for leaving the Islamic State aren't always clear. What convinced me that, as a whole, their stories are credible is how consistent their messages were.

Among the 58 defector stories, I found four narratives that were particularly strong:

One of the most persistent criticisms was the extent to which the group is fighting against other Sunni rebels. According to the defectors, toppling the Assad regime didn't seem to be a priority, and little was done to help the (Sunni) Muslims who were targeted by it.

Most of the group's attention, they said, was consumed by quarrels with other rebels and the leadership's obsession with "spies" and "traitors." This was not the kind of jihad they had come to Syria and Iraq to fight.

Another narrative dealt with the group's brutality. Many complained about atrocities and the killing of innocent civilians. They talked about the random killing of hostages, the systematic mistreatment of villagers and the execution of fighters by their own commanders.

None of the episodes they mentioned involved minorities, however. Brutality didn't seem to be a universal concern: it was seen through a sectarian lens, and caused outrage mostly when its victims were other Sunnis.

The third narrative was corruption. Though none believed that corruption was systemic, many disapproved of the conduct of individual commanders and "emirs." Syrian defectors criticized the privileges that were given to foreigners, for which they claimed was no justification based on the group's philosophy or Islam in general.

While many were willing to tolerate the hardships of war, they found it impossible to accept instances of unfairness, inequality and racism. "This is not a holy war," said a defector from India, whom the group had forced to clean toilets because of his color of skin.

A fourth narrative was that life under the Islamic State was harsh and disappointing. The defectors who expressed this view were typically the ones who had joined the group for "selfish" reasons -- and who quickly realized that none of the luxury goods and cars that they had been promised would materialize.

For others, their experience in combat didn't live up to their expectations of action and heroism. One of them referred to his duties as "dull" and complained about the lack of deployments, while another claimed that foreign fighters were "exploited" and used as cannon fodder.

These stories matter. The defectors' very existence shatters the image of unity and determination that the group seeks to convey. Their narratives highlight the group's contradictions and hypocrisies. Their example may encourage others to follow, and their credibility can help wannabes from joining.

In my view, governments and civil society should recognize the defectors' value and make it easier for them to speak out. Where possible, governments should assist them in resettlement and ensure their safety. They also need to remove legal disincentives that prevent them from going public.

Not every defector is a saint, and not all of them are ready or willing to stand in the public spotlight. But their voices are strong and clear: "The Islamic State is not protecting Muslims. It is killing them." They need to be heard.

Stay Updated And Connected With sofogist.Com Daily..

Stay Updated And Connected With sofogist.Com Daily..