Roel Foppen/ Stichting Ambulance Wens

Roel Foppen/ Stichting Ambulance Wens

Earlier this year a photograph was released showing a woman on a stretcher in Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum. She was there to take a final look at her favourite Rembrandt painting. Her visit had been made possible by a Dutch charity that helps terminally ill patients fulfil their last wish.

"I've learned that people who are going to die have little wishes," says Kees Veldboer, the ambulance driver who founded the Stichting Ambulance Wens - or Ambulance Wish Foundation - after an impulse to help a patient.

In November 2006 he was moving a terminally ill patient, Mario Stefanutto, from one hospital to another. But just after they put him on the stretcher, they were told there would be a delay - the receiving hospital wasn't ready. Stefanutto had no desire to get back in the bed where he had spent the past three months, so Veldboer asked if there was anywhere he would like to go.

The retired seaman asked if they could take him to the Vlaardingen canal, so he could be by the water and say a final goodbye to Rotterdam harbour. It was a sunny day, and they stayed on the dockside for nearly an hour. "Tears of joy ran over his face," says Veldboer. "When I asked him: 'Would you like to have the opportunity to sail again?' he said it would be impossible because he lay on a stretcher."

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Veldboer was determined to make this man's last wish come true. He asked his boss if he could borrow an ambulance on his day off, recruited the help of a colleague and contacted a firm that does boat tours around Rotterdam harbour - they were all happy to help, and the following Friday, to Stefanutto's astonishment, the ambulance driver turned up at his hospital bedside to take him sailing.

In a letter written weeks before his death Stefanutto wrote, "It does me good that there are still people who care about others… I can tell you from my own experience that a small gesture from someone else can have a huge impact."

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Stichting Ambulance Wens

That was the genesis of the Stichting Ambulance Wens. Veldboer and his wife Ineke, a nurse, started it at their kitchen table - eight years on it has 230 volunteers, six ambulances and a holiday home, and is fast approaching 7,000 fulfilled wishes. Sometimes wishes are fulfilled the day they are made. On average, the charity helps four people a day - they can be any age and the only stipulation is that patients are terminally ill and can't be transported other than on a stretcher.

"Our youngest patient was 10 months old, a twin. She was in a children's hospice and had never been home - her parents wanted to sit on the couch with her just one time.

"And our oldest patient was 101 - she wanted to ride a horse one last time. We lifted her on to the horse with the help of a truck, and later we moved her to a horse-drawn carriage - she was waving at everyone like royalty. That was a good wish," says Veldboer.

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Although other charities offer terminally ill patients a day out, the Stichting Ambulance Wens was the first to provide an ambulance and full medical back-up. There is always a fully-trained nurse on board, and the specialist drivers tend to come from the police and fire brigades. The specially-designed ambulances have a view, and every patient receives a teddy bear called Mario, named after Stefanutto.

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Find out more

- Kees Veldboer spoke to Outlook Listen to the interview on iPlayer

- Listen to more extraordinary stories from Outlook on the BBC World Service

"It gives us volunteers so much satisfaction to see people enjoying themselves," says Roel Foppen, a former soldier who acts as a driver. Over the past six years he has helped to fulfil 300 wishes.

Once he went as far as Romania, a 4,500km (2,800 mile) round-trip. It was for a woman called Nadja, who had lived in the Netherlands for 12 years. Her children, aged three and seven, were already back in Romania with her family, and she wanted to go there to die.

"She was so ill we couldn't even touch her," says Foppen. They left on a Thursday morning, but as they were driving through Germany Nadja's condition deteriorated, so they stopped at a hospital. Doctors recommended Nadja stay there, but she wanted to see her children - and her wish was what counted. After a three-hour delay they carried on, through Austria, then Hungary - when they reached the Romanian border, Nadja said, "Take the stretcher out, now I can die!"

Foppen said, "It's just another 600km to your mother and your children - could you hang on just a little longer?" On the Saturday the ambulance arrived in Bucharest for an emotional reunion. Then the crew drove back, leaving Nadja behind. Her family sent a card to say she died two weeks later.

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Stichting Ambulance Wens

"If people know we're coming, they find new reserves of energy," says Foppen. "Often the family tell us they were about to cancel because the patient was so ill, but when we arrive they are beaming, ready for their day out."

It was Foppen who took the famous photograph in the Rijksmuseum. He was on the other side of the gallery with his colleague Mariet Knot, fulfilling someone else's wish. They were looking after a man called Donald, who used to visit the museum regularly with his partner of 30 years - the two men had married the week before. "What was great was that he was very much in charge," says Knot. "He told us which paintings he wanted to see and was able to tell us a lot about them, so we could enjoy it too."

The last work in the exhibition was one Donald had never seen before - Simeon with the Christ Child in the Temple, a painting that remained unfinished at the time of Rembrandt's death. Donald was deeply moved by it. "I realise now that a life is never finished. My life is unfinished, and this painting is unfinished," he told them.

Then, after a pause, "I have seen what I wanted to see, we can go now."

Bridgeman Art Library

Bridgeman Art Library

Knot, who works as a district nurse, says it is an honour to be able to share such moments. She first came across the charity when she was invited along by a cancer patient she had grown close to. His wish was to see the Maasvlakte 2, a major new extension to Rotterdam's port which is being built on reclaimed land. Before he got too ill, he would check on its progress every week - this time he was given a grand tour. The experience made Knot so enthusiastic she wrote to Veldboer to offer her services.

"Every time is special. You discuss it with your colleagues on the way home and it's always special, no matter how small," says Knot. "I had one lady who just wanted a glass of advocaat (a thick egg liqueur) at home. So her son bought a bottle, we went to her house, she spooned up the advocaat and we went back. That was her wish."

"People ask, 'Isn't it draining? Isn't it emotional, always dealing with last wishes?' Yes it is, but often people are ready to die because they are so far down the line, and then it's nice to give them something they really want," she says.

Frans Lepelaar is a former policeman who now drives for the charity. After 20 years behind a desk, investigating fraud, he wanted to get back to helping people face-to-face. "Sometimes it is difficult, but as a policeman I also had to deal with murder so I know how to take a step back," he says.

"It can be a long day - you could be back in the middle of the night. We always ask, 'Do you want anything more?' They're always grateful. That's what you do it for," he says.

A great deal of wishes involve going home, saying goodbye to colleagues or attending weddings and funerals. Many long to see the sea, "because it's part of the Dutch landscape" says Lepelaar, who used to patrol the beach. Zoo trips are also very popular, and make up about 15% of the wishes.

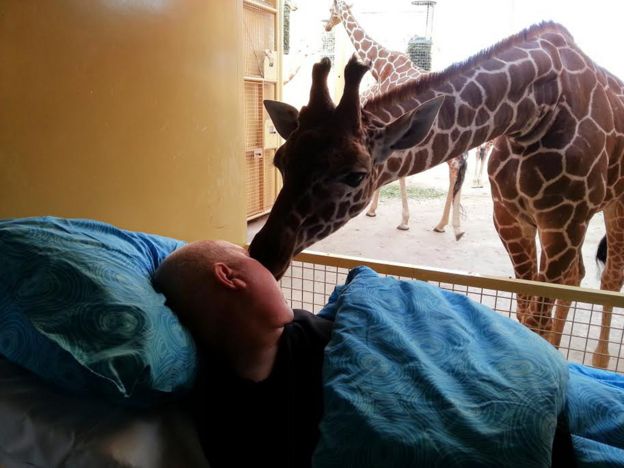

It was one such trip that made headlines in 2014. Lepelaar and his colleague Olaf Exoo took Mario, a 54-year-old man with learning difficulties, to say a final goodbye to his colleagues at Rotterdam's Diergaarde Blijdorp Zoo, where he had worked for 25 years. At the end of his shift as a maintenance man he used to always visit the animals, and they took him on his rounds one last time.

When they reached the giraffe enclosure they were invited in, and it was then that one of the more curious giraffes came over and gave Mario a lick on the face. He was too ill to speak, but his face lit up, says Exoo, whose photograph of the "giraffe's kiss" made headlines.

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Exoo says he likes the little wishes best. "Those things that we take for granted, but which have become impossible for these people." As his own nursing career progresses, Exoo spends more and more time behind a desk, so volunteering is a way of getting back to what he loves best - caring for patients. "There are no time limits, so I can spoil people all day long," he says.

"It's intense, but that's why it's interesting," says Mirjam Lok, a 25-year-old nurse. "You don't know who you'll meet when you walk through the door, and at the end of the day you have fulfilled their last wish, you close the door and you think - that was good.

"It has taught me that you can find happiness in little things, and that's what you should aim for - rather than longing for what you don't have."

Lok is based in the north of the country, and had hoped to work locally, but it seems that very few people in the northern provinces - Groningen and Friesland - have last wishes. "They are very phlegmatic," says Lok. "People don't ask for much, they are easily satisfied - they say, 'I wouldn't know what my last wish could be.'"

Veldboer confirms that fewer northerners use their services, and the same applies to the southern province of Zeeland. He thinks it's a question of regional character, but Knot believes it's more about medical staff encouraging patients to take up the offer.

At first, doctors would veto the foundation's outings, says Veldboer, but as their work has become better known, this happens very rarely. Now it's often the hospital or hospice that makes the first move.

"There was one lady who wanted to go to her grandson's wedding. The hospice had told her 'No', but she was desperate, so in the end they called us. We took her there and she loved it," says Veldboer. "On the way home she turned to us and said, 'You don't realise how important this was to me.'" She died that same night.

Considering how close to death their patients are, it is perhaps surprising that out of nearly 7,000 guests only six have died during their "wish". In those cases the role of the ambulance crew is to support the family, and to make the necessary arrangements for the body. Veldboer says that in all six cases the families were grateful for their help.

Stichting Ambulance Wens

Stichting Ambulance Wens

"I think we have come a long way with palliative care and end-of-life care," says Knot. "We make sure people have no pain. They have stopped receiving treatment, and they are going to die soon... if they can have a nice day out, even if they're tired the next day, isn't that a good thing? Everyone is happy to work towards that."

"In the Netherlands discussions about death are more and more open," says Knot. As part of her work as a district nurse she often asks about final arrangements, sedation and euthanasia - usually patients have already talked about these things with their doctors.

"I do think there has been a change of culture - for older people, especially if they grew up in the church, it's still swept under the carpet, it gets tucked away, but for younger people with a family it is spoken about openly," she says.

Knot believes what the foundation does is very much part of the grieving process, and that it's good to involve patients while they are still able - "so it doesn't have to wait until after their death".

As an example she cites a man whose last wish was to go back to the family firm. "The whole family came to the warehouse to say goodbye to this man on a stretcher. He wanted to go and see all the machines, revisit all the dark corners where he had fixed things." While they wheeled the stretcher through the warehouse the rest of the family followed, in a sort of procession. "It was tiring for him to talk, because he used sign language - he and his three brothers were all deaf, as were two of their wives," says Knot. "Then my driver began speaking with his hands." The ambulance driver, who was new to the foundation, knew sign language. "It was so extraordinary, the family said they got goose bumps. Then you think - there is no such thing as coincidence."

Following the huge success of his venture, Veldboer has helped to set up similar ambulance services abroad, first in Israel - after taking a Jewish woman to Jerusalem, where she wanted to die - then in Belgium, Germany and Sweden.

A practical, no-nonsense man, he admits that setting up the foundation has given him confidence. "I used to think I didn't amount to much, but then I discovered my ideas aren't that bad after all. I've learned that if you follow your heart and do things your own way, people will support you.

"I'm just a very ordinary Dutch guy who does what he likes best, and my hobby is helping others."

Stay Updated And Connected With sofogist.Com Daily..

Stay Updated And Connected With sofogist.Com Daily..